Clothes and Controllers

The Mother Machine: Pillars for reliability in bioengineering

Dear SoTA,

With the winter now in full swing, I would like to ask: how do you find a balance between wearing clothes and staying warm outside?

If your answer is ‘this question makes no sense’, you have given the right answer. Balancing an action and its purpose is an oxymoron, because wearing warm clothes is exactly how you stay warm. Let us move to the next question: how do you find a balance between innovation and safety?

If your answer is not the same as before, why? Innovating is exactly how we make people’s lives easier, happier, healthier – and yes, safer. Of course, you could create an invention which makes life easy but is unsafe, just like you could wear a shirt that looks fabulous but is not warm at all. But if you walk in the snow with nothing but your stunning shirt on, you will look stupid. Put something else on top, it’s freezing out here! When you deploy an unsafe invention, you look just as stupid. Have a safeguard, you’re endangering yourself and others!

Running around naked, however, is an even worse way to stay warm. We are facing unprecedented risks in all spheres – changing climate, failing healthcare, unsustainable and fragile supply chains… And we will need innovation to tackle them. However, we should be dressing thoughtfully, and designing systems with safety in mind from the start.

I am proud to be part of a community which applies this thinking to Engineering Biology. The EEBIO Programme Grant is a consortium of academics from Imperial College London, the University of Bristol, and the University of Oxford (as well as a range of industrial partners) working to make engineered cells reliable, predictable and robust to potential disruptions. A future where manmade biological systems are controllable and safe rests on four pillars: sound theory of how they work, usable software to help design them, ‘wetware’ (the actual DNA sequences we put into cells to engineer them), and hardware interacting with our cells. In building these pillars, we as bioengineers are taking pages out of other engineers’ playbooks – most notably, control theorists, whose bread and butter is designing systems with robustness and safety guarantees.

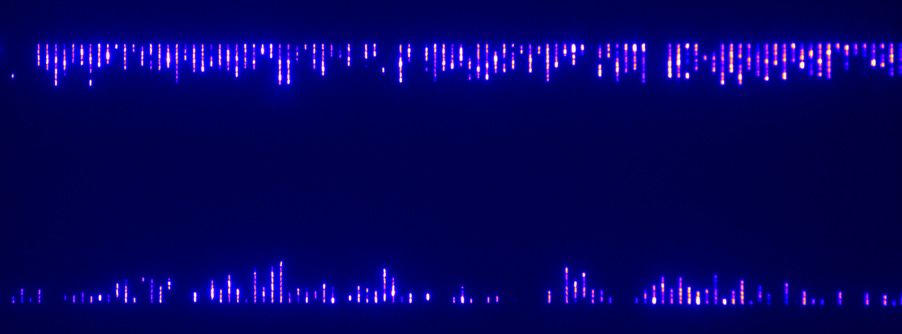

What does this mean in practice? It starts with actually knowing how your system will behave once created, which is easier said than done. Complex biological designs (think biosensors, bacteria acting as a living therapeutics, etc.) usually involve combining several genes in the same cell, each executing its own function to achieve the ultimate performance goal. But life is messy, so you’re bound to see your genetic components interacting in ways you never intended! That is, if you don’t characterise the possible ways these interactions may arise. My work at EEBIO aims to develop such a characterisation method for all biosystem components. To this end, we add a gene of interest to bacteria, then put them in a ‘Mother Machine’ chip, which allows to observe live individual cells in a microscope and automatically control them using light and chemical inputs. Dynamically adjusting the inputs, we make sure that throughout the experiment we observe all possible ways in which a gene can interact with other system components. The outcome? A comprehensive dataset allowing to accurately predict how our gene will behave when combined with any other gene characterised in a similar manner.

Fig 1: Bacteria in a Mother Machine chip.

My project is just one among many things we are building at EEBIO. If you are interested in engineering biological systems which are reliable and actually work as intended, reach out at eebio.ac.uk

Dress to stay warm. Innovate to be safe.

Best,