How I built a line sensor that was used in pro squash tournaments

With a little help from a professor, a technician, and a cracked electrical engineer

Dear SoTA

I'm an avid squash player and viewer of pro squash. As in all racquet sports, it can sometimes be hard to tell if the ball is out. This creates problems for both referees and players.

Let’s think about glass courts. How can we solve the problem of knowing whether the ball is out? Simple: run a laser laterally. over the top of the line. The laser meets a sensor at the other end. If the ball brushes the line, it blocks the laser. The sensor registers the blockage. You therefore know when the ball is out.

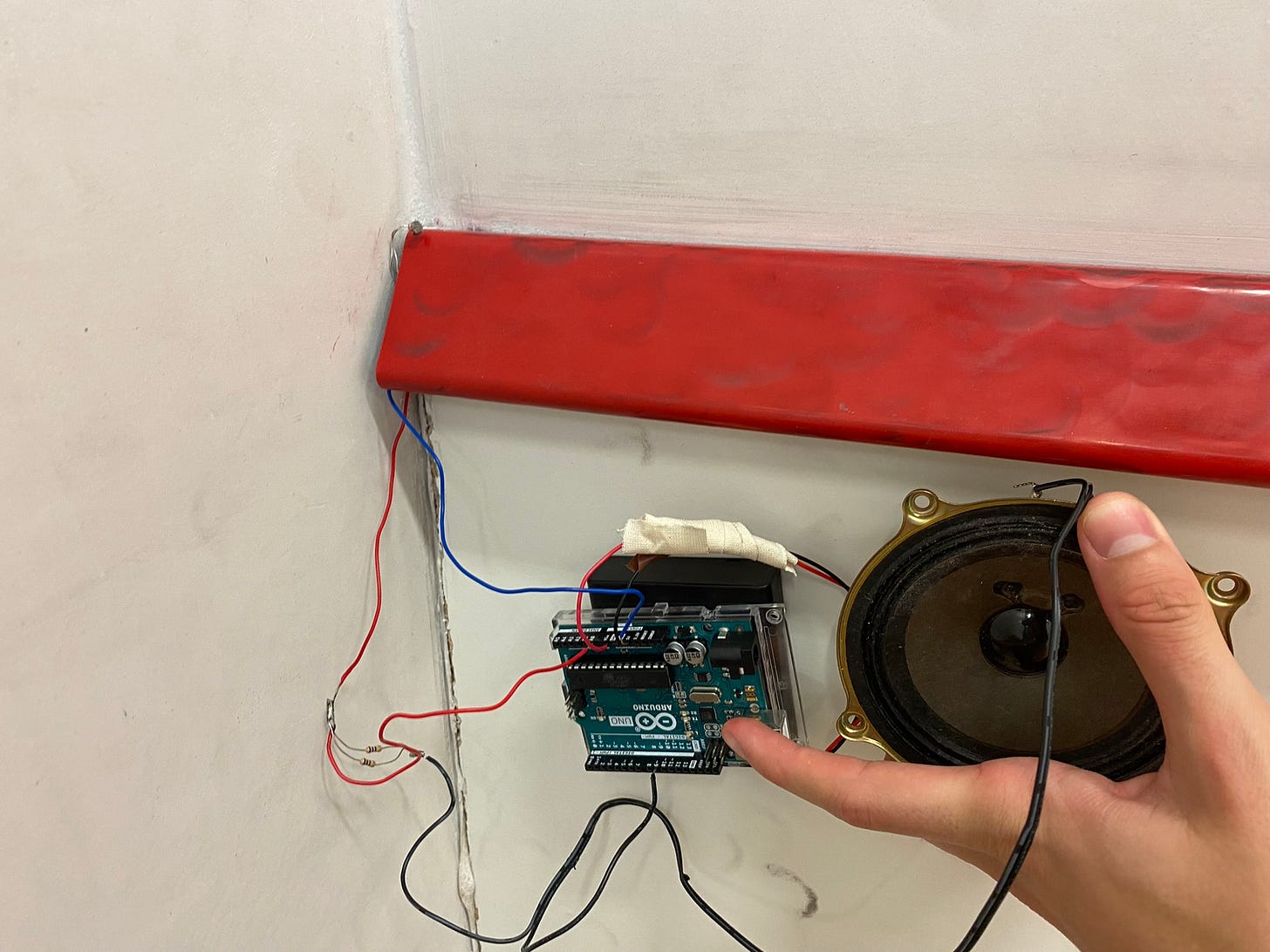

I started this project at university. Here's the first shitty little tester that I taped to my local court to get a feel for the problem space. The two main issues became abundantly clear: (1) vibration generated by play resulted in false positives; (2) it wasn’t cheap to align the laser.

The device…

And the laser…

I had a meeting with the MechEng professor who ran the business class. I told him that I was looking at building a proper prototype. The absolute boss gave me £500 of department money to try and build this. After I met with the PSA (Professional Squash Association). They agreed to let me run a trial at a pro tournament.

But I had to finish the sensor first. Here commenced two months of insanity where I had to design and build this prototype from scratch. I barely went to lectures, just built.

To solve the alignment problem (so to speak) I needed something for micro adjustment in 2DoF translation. A cheap macro-photography tool accomplished that. The much harder problem was 2DoF angle change. This was hard because I needed to get it to an obscene level of precision, 0.001 degrees, and the only tools for this were way outside my budget...

I went to a technician for advice: could I potentially make a rough version of the tool myself? Probably not in time. As I described the tool to him, he went: "Oh, you mean one of these," and whipped two of them out of his desk drawer. My jaw hit the floor. They were from some previous physics experiment. He gave them to me and I was sorted.

All I needed to do to solve the vibration problem was to put a fat, heavy base on the laser. I was running out of time. The day before I was meant to have my first test in the National Squash Centre, I was trying to get the base waterjet cut. The cutter broke in the middle of doing of my part...

The same technician – I love him – took the sheet, and we managed to angle grind and bend it into just about the right shape. Then I fill it with quickset concrete and embed the tripod. Voilà.

The sensor, thankfully, had fewer issues. With the help of a cracked electrical engineering buddy, who I later partnered with, I got it working with with time to spare. The only notable issue was that the latency of LDRs actually mattered... so we had to use phototransistors.

The first test in Manchester went to plan – so I was ready for the trial two weeks later. It was in Canary Wharf, in London, in an exhibition match before a final. I set up the device and watched the venue fill up with 500 people. I was shitting myself as they announced my name and explained to the crowd that the sensor was being trialled for the first time.

Luckily, it all went to plan.. The device worked perfectly.

Of course it was rushed, and the whole thing looked like shit. So after I graduated from uni, I found a workshop in London where I could fix it up.

Squaser V2 was much nicer. I covered up the steel with sexy black acrylic, and I partnered with the cracked EE who remade the sensor. We were ready for the second trial, this time at the Optasia Squash Championships. It would be used by referees during actual matches.

The first day went well. The device adjudicated some calls and the referees were happy. I was set to continue for the whole week of the tournament. Then, on the second day, the battery in the sensor went faulty – and I didn’t have a spare. It stopped working in the the last match before the tournament’s lunch break. Cue me cycling around Wimbledon in a mad rush trying to find a vape shop for an 18650 battery.

Luckily, I found one. The rest of the tournament went smoothly. Here's a video compilation of the calls the device made.

Over the course of this whole thing I managed to win £10k in engineering prizes, met some incredible people, including some of my squash pro idols, and learned as much through the entire process as my whole degree.

I wanted to have Squaser used in every tournament and become a staple on the tour, helping referees and players and making the game more fair. But it looks to have fizzled out. The PSA have lost interest, unfortunately, and now I'll be starting my masters in Innovation Design Engineering at the Royal College of Art and Imperial.

It's been an incredible journey. This is the work I'm most proud of. And it's just the beginning of many more interesting things to come...

Yours

Gruffydd Gozali

Write your own letter to SoTA by emailing info@ilikethefuture.com