Predictive Infrastructure for Nature

How an FRO can build the Global Nature Data Observatory

Dear SoTA,

History shows that every time we have successfully modelled a complex natural or human system, it has triggered profound shifts in technology, economies, and collective understanding. Take the weather. Until the mid-20th century, storms were unpredictable killers until we built global weather models, assimilated data, launched satellites, and enabled numerical forecasting. Today, in the UK alone, weather prediction creates over £1.1 billion of economic value every year (i.e. through helping industries adapt operations: energy, shipping, aviation, rail, etc.) (Frontier Economics et al., 2024). Globally, effective weather forecasting underpins trillions in agriculture, insurance, energy, logistics, aviation, and disaster response. Every time we gain predictive visibility into a major system, new patterns emerge, industries reorganize, risks get priced, new markets appear, and entire scientific fields unlock.

If you ask what the next complex system is that we must make more understandable and predictable, many will point to microscopic systems such as cells, or to large-scale systems like energy demand for AI infrastructure, or even to the urban environments we navigate every day. But we think the answer is right under our feet. Our ecosystems, soils, wetlands, grasslands, rivers, determine our food security, water availability, carbon balance and economic stability. 75% of the UK economy is exposed to financial risks tied directly to the health of nature (Green Finance Institute et al., 2024).

So why is there such a gap in our understanding? We have global remote sensing capability that is rapidly becoming more accessible via shared data infrastructure and standards (e.g. Brown et al., 2025; Clay, 2025; Stewart et al., 2023). We have powerful deep learning models that can use ground truth data to interpret remote sensing data and predict continuous layers of species distributions, ecosystem functions, ecosystem services etc. (Davis et al., 2023; Dinnage, 2024; Gillespie et al., 2024; Harrell et al., 2025; Seo et al., 2021). We have an increasingly powerful capacity to rapidly and simultaneously generate coupled biodiversity and environmental-covariate datasets (Hartig et al., 2024). These are now sufficiently scalable to generate a multimodal ground truth dataset that spans the full Ecosystem Condition Typology (ECT+) (Czúcz et al., 2021) covering all dimensions of ecosystems: abiotic, biotic, landscape-level, and anthropogenic pressures and drivers.

However, despite these technological advancements, there does not now exist anywhere a dimensionally comprehensive ground truth dataset of overlapping biodiversity and ecosystem condition measures large enough to utilise and train novel AI tools, much less high-resolution time series of the same. For example, even the largest existing biodiversity reference datasets are still taxonomically and geographically narrow (e.g. only birds in North America or only plants in Europe (Brun et al., 2019; Callaghan et al., 2021; Sullivan et al. 2009; ). In contrast, while remote sensing has allowed the production of public and global data products that measure some aspects of aboveground ecosystem structure and function, many belowground, biochemical, or interaction-based processes are missing (Pettorelli et al., 2018), leaving major dimensions of Ecosystem Condition (approximated as “health”) unobserved.

A Focused Research Organisation (FRO) is uniquely suited to overcome the technical challenges to standardized, scalable, and reliable ecological monitoring and modelling. Academia excels at deep insight and specialised expertise, but not at building decade-long infrastructure, since publishing and its requisite methodical and short-term schedule remains the dominant metric of success. Venture capital-backed industry, meanwhile, excels at rapidly scaling products in known markets but rarely funds the kind of high-risk and open-access efforts needed to catalyse scientific innovation, even if they may seed a future field of research or encourage a nascent market. FROs fill the gap between academic labs and commercial startups: large enough to pursue ambitious, multi-year goals, but mission-driven rather than profit-driven. They have the perfect structure to create public-benefit infrastructure (datasets, platforms, measurement systems, foundational models) that no single lab can sustain and no company would build openly. FROs blend the scientific depth of academia with the operational discipline of industry: stable teams, strong engineering, dedicated program management and long-time horizons. Unlike startups, they need not commercialise their outputs; unlike academia, they are not constrained by short grant cycles. This makes them uniquely capable of tackling problems (like ecological prediction) that require coordinated data generation, tight integration of science and engineering, and institutional continuity over many years.

We are a part of the first ARIA-Convergent Research cohort to build UK-based FROs and have spent the past six months in a Founder-in-Residence programme shaping the UK-FRO direction. UK’s first FRO effort, Bind Research, launched in 2025 to transform disordered proteins into viable drug targets. Our upcoming cohort explores numerous exciting ideas including compressing large data, AI security, brain connectomics, and improving the state of our ecosystems. This is where, amongst others, the concept behind ECHO (Ecosystem Characterisation for Hybrid Observation) took form. ECHO’s mission is to build the foundational infrastructure that ecological prediction requires:

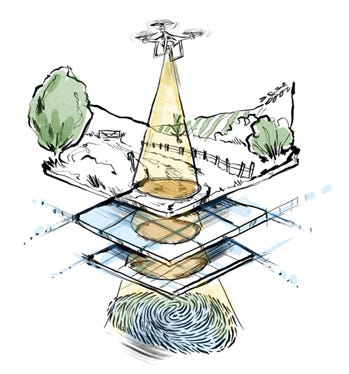

A unified data foundation specifically designed to capture signals of ecosystem change, integrating co-located soil sensors, bioacoustics, imagery data across thousands of UK sites into a harmonised dataset designed for joint analysis with Earth observation.

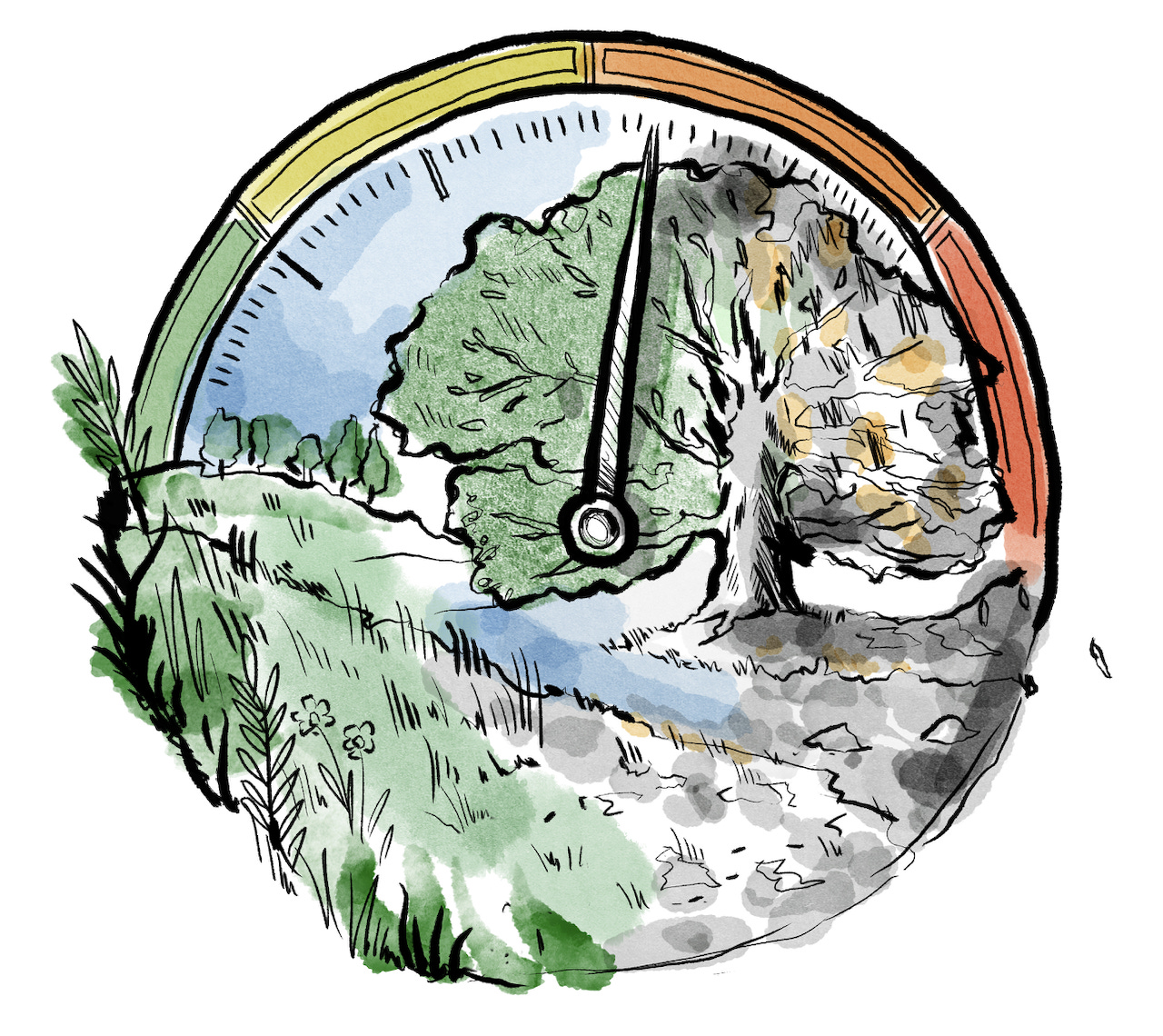

A dynamic modelling framework using machine learning to convert static snapshots into predictive “ecosystem fingerprints,” tracking Ecosystem Condition across space and time.

A transferability framework testing how Ecosystem Condition models generalise across scales, ecosystem typologies, and data densities, identifying pathways for efficient scaling, operational deployment, and a proof of concept for decision-making across restoration initiatives, risk management, and policy.

ECHO is intentionally designed to transform beyond the short (usually five-year) lifetime of the typical FRO. Its transition goals aim to support a Global Nature Data Observatory, akin to a “UK Biobank for Nature”. The new entity would be governed like a cooperative utility and operate with tiered licensing to balance open access with long-term financial sustainability, ensuring that academic use remains free while commercial access supports maintenance and growth.

For the United Kingdom, this model offers immense opportunity for national benefit and the UK is uniquely positioned to host this effort. The regulatory landscape, from Biodiversity Net Gain to the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), have created the most advanced policy environment in the world for integrating nature risk into decision making. Simultaneously, the country’s productive landscapes are the most intensively modified in Europe, with three quarters of the economy directly exposed to nature-related risks. These long-standing biodiversity deficits make the need for detection of resilience signals and early ecological change even more acute.

Parametric insurance providers, agriculturally exposed banks, and infrastructure-sector organisations have already expressed their interest in quantifying Ecosystem Condition as a risk-modulating asset, and will be involved from the onset to ensure that ECHO’s science translates to economic impact. We expect that the resulting capability that we are developing at ECHO will equip policymakers, regulators, investors, and utilities with decision-grade ecological intelligence, supporting new policy and market paradigms that align economic growth with ecological resilience.

Regards,

Dr. Wasik is a founder in residence Convergent Research FROST-UK program and entrepreneur in residence at Ahren Innovation Capital.

References

Davis, C. L., Bai, Y., Chen, D., Robinson, O., Ruiz‐Gutierrez, V., Gomes, C. P., & Fink, D. (2023). Deep learning with citizen science data enables estimation of species diversity and composition at continental extents. Ecology, 104(12), e4175. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.4175

Dinnage, R. (2024). NicheFlow: Towards a foundation model for Species Distribution Modelling (No. 2024.10.15.618541; p. 2024.10.15.618541). bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.15.618541

Gillespie, L. E., Ruffley, M., & Exposito-Alonso, M. (2024). Deep learning models map rapid plant species changes from citizen science and remote sensing data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(37), e2318296121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2318296121

Harrell, L., Kaeser-Chen, C., Ayan, B. K., Anderson, K., Conserva, M., Kleeman, E., Neumann, M., Overlan, M., Chapman, M., & Purves, D. (2025). Heterogeneous graph neural networks for species distribution modelling (No. arXiv:2503.11900). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.11900

Hartig, F., Abrego, N., Bush, A., Chase, J. M., Guillera-Arroita, G., Leibold, M. A., Ovaskainen, O., Pellissier, L., Pichler, M., Poggiato, G., Pollock, L., Si-Moussi, S., Thuiller, W., Viana, D. S., Warton, D. I., Zurell, D., & Yu, D. W. (2024). Novel community data in ecology – properties and prospects. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 39(3), 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2023.09.017

Seo, E., Hutchinson, R. A., Fu, X., Li, C., Hallman, T. A., Kilbride, J., & Robinson, W. D. (2021). StatEcoNet: Statistical Ecology Neural Networks for Species Distribution modelling (No. arXiv:2102.08534). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2102.08534

Sullivan, B. L., Wood, C. L., Iliff, M. J., Bonney, R. E., Fink, D., & Kelling, S. (2009). eBird: A citizen-based bird observation network in the biological sciences. Biological Conservation, 142(10), 2282–2292.